Circumcision in Berkshire & Windsor, Urology Now

Circumcision in the male refers to the surgical removal of the prepuce (ie, foreskin) of the penis. This is a very safe and effective procedure that is centuries old and continues to be performed for a variety of religious, cultural, and medical reasons.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The United States is the only country in the developed world where the majority of male infants are circumcised for nonreligious reasons. This is not the case in the United Kingdom where Circumcision is generally reserved for medical reasons. The overall circumcision rate in the United States is estimated to be about 80 percent for males aged 14 to 59 years, with most of these procedures performed in newborns [1]. Circumcision rates outside of the United States vary widely, from less than 5 percent to over 90 percent of males [1]. An Australian survey found that approximately 18 percent of males who were not circumcised as infants reported that they needed to be circumcised subsequently for medical reasons [2].

NORMAL DEVELOPMENT AND ANATOMY

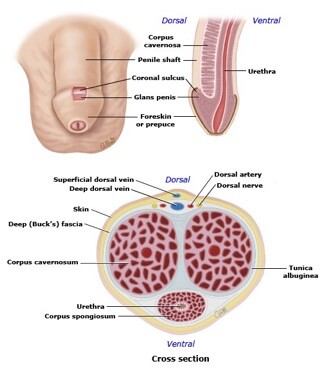

The penis consists of a proximal root, middle body (corpus or shaft), and distal head (glans). The prominent circumferential rim where the glans begins is called the glans corona, and the constriction just below the corona is the coronal sulcus (figure 1).

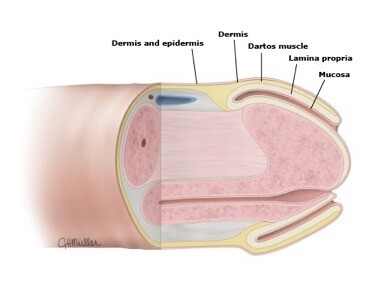

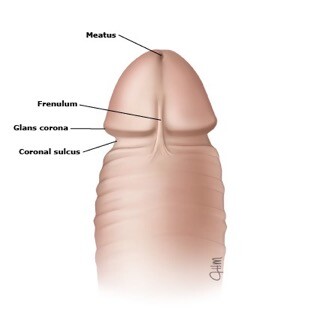

The skin of the body of the penis starts to grow over the glans between 10 and 18 weeks of gestation, eventually covering the entire organ. The prepuce is a specialized, junctional mucocutaneous tissue that forms the transition between the mucosal epithelium of the glans and the keratinized epithelium of the penile shaft, analogous to the eyelids. The double sheet of prepuce covers the glans for a variable distance and consists of several thin layers: inner squamous epithelium (mucosa), lamina propria, dartos muscle, dermis, and outer keratinized stratified squamous epithelium (figure 2). The frenulum is a ridge of tissue that extends from the base of the prepuce at the coronal sulcus to a point just inferior to the external urethral orifice (meatus) (figure 3). It is supplied by the frenular artery and vein, which can cause significant bleeding if disrupted during circumcision.

At birth, the prepuce is fused to the glans by filmy adhesions that prevent retraction (congenital or physiological phimosis). These adhesions resolve over time due to desquamation and epidermal keratinization. The resulting separation of the prepuce and the glans is called the preputial space and allows easy retraction.

Separation is completed in 50 percent of boys by age 3 years, 95 percent by age 5 years, and 99 percent by adolescence. In a small number of uncircumcised males, partial adhesions leading to accumulation of smegma may persist throughout childhood, and even into adolescence.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the penis.

Figure 2. Development of the foreskin

COUNSELING

Patients and their parents should receive factually correct, nonbiased information about the potential medical benefits and risks of circumcision and should understand that the procedure is elective.

POTENTIAL BENEFITS

Circumcision has been associated with a number of medical benefits, including lower rates of urinary tract infection (UTI), penile cancer, penile inflammation, penile skin problems (dermatoses), and sexually transmitted infections. The commonest indication in the UK is pathological phimosis where there is an inability to retract the foreskin due to disease in the foreskin. Other medical indications include inability to replace the foreskin after it has been retracted (paraphimosis) and recurrent splitting of the foreskin or the frenulum.

In the uncircumcised male, the preputial space provides a warm moist environment that both traps pathogens and bodily secretions and is favourable to their survival and replication, while the foreskin itself is susceptible to micro-abrasions that are thought to facilitate acquisition and transmission of infection. In contrast, the keratinized glans of the circumcised male is thought to create a more unfavourable environment for these processes.

Reduction in urinary tract infection — UTI is uncommon in males at any age. The effect of circumcision on

UTI has been studied primarily in infants because they have a higher prevalence of UTI than older males. UTIs in infants can result in pyelonephritis requiring hospitalization and, rarely, septicaemia and death. In infants with congenital anomaly of the renal tract, UTI can have serious sequelae, such as renal scarring and lifelong renal insufficiency. If the urinary tract is normal, long-term sequelae from UTI are unlikely. Comparative studies consistently report that circumcised male infants under the age of 1 have significantly fewer UTIs than uncircumcised male infants [3], with a risk reduction of UTI by almost 90 percent (OR 0.13,

95% CI 0.08-0.20) [18]. The prevalence of UTIs in uncircumcised adult males increases with age and certain disease states, such as diabetes mellitus [4].

Reduction in risk of some cancers — Compared to uncircumcised men, circumcised men appear to have a lower risk of penile cancer, and their sexual partners may have a lower risk of cervical cancer.

Penile cancer — Squamous cell cancer of the penis is a rare disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis found a strong protective effect of childhood/adolescent circumcision on invasive penile cancer (OR 0.33;

95% CI 0.13-0.83; 3 studies) [5].

Cervical cancer in partners — Cervical cancer is more common in the sexual partners of uncircumcised men.

A partial explanation for the link between cervical cancer and lack of male circumcision is that circumcised men have a lower prevalence of HPV infection than uncircumcised men, they are less likely to transmit HPV to their partners, and their partners have lower high-risk HPV DNA load [6].

Reduction in sexually transmitted infections — There is high quality evidence that circumcision protects against acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HPV, and probably herpes simplex virus type 2

(HSV-2) [7], and also some evidence that it may protect against trichomonas and chancroid infection as well

[8]. Circumcision does not protect against infection from gonorrhea, chlamydia trachomatis, or syphilis [9].

What happens during the procedure?

A full general anaesthetic is normally used and you will be asleep throughout the procedure. A local anaesthetic injection around the penis may also be used. Your anaesthetist will explain the pros and cons of each type of anaesthetic to you.

Local anaesthetic is injected into the base of the penis to relieve discomfort after the operation. This can be used as the sole form of anaesthesia in some patients. All methods minimise postoperative pain.

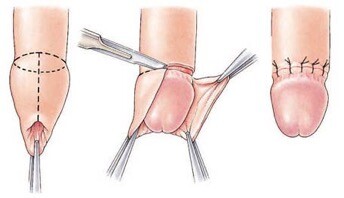

The entire foreskin will be removed using an incision just behind the head of the penis (pictured). This leaves the head of the penis completely exposed with no redundant skin.

Figure 3. Operative technique of circumcision (Sleave).

Complications

Careful, meticulous attention to penile anatomy (figure 1) and the correct use of surgical equipment by trained clinicians can prevent most complications from circumcision. Most patients are very happy with the long term results. However, there is a small risk of complications which are very low in the neonatal period and slightly higher as the patient gets older [10].

The most common complications of male circumcision are bleeding and local infection, followed by unsatisfactory cosmetic results (too little or too much skin removed) and surgical trauma or injury. Rare, but significant complications include life-threatening sepsis and meningitis, buried penis due to cicatrix formation, amputation of the glans, and necrotizing fasciitis.

Common (greater than 1 in 10)

- Swelling of the penis lasting several days.

Occasional (between 1 in 10 and 1 in 50)

- Bleeding of the wound occasionally needing a further procedure.

- Infection of the incision requiring further treatment and/or casualty visit.

- Permanent altered or reduced sensation in the head of the penis.

- Persistence of the absorbable stitches after three to four weeks, requiring removal.

Rare (less than 1 in 50)

- Scar tenderness.

- Failure to be completely satisfied with the cosmetic result.

- Occasional need for removal of excessive skin at a later date.

- Permission for biopsy of abnormal area on the head of the penis if malignancy is a concern.

Figure 4. Diagram of circumcised penis

References

- Morris BJ, Bailis SA, Wiswell TE. Circumcision rates in the United States: rising or falling? What effect might the new affirmative pediatric policy statement have? Mayo Clin Proc 2014; 89:677.

- Badger, J. The great circumcision report part 2. Australian Forum 1989; 2:4.

- Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, Farrell MH. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta- analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008; 27:302.

- Spach DH, Stapleton AE, Stamm WE. Lack of circumcision increases the risk of urinary tract infection in young men. JAMA 1992; 267:679.

- Larke NL, Thomas SL, dos Santos Silva I, Weiss HA. Male circumcision and penile cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2011; 22:1097.

- Davis MA, Gray RH, Grabowski MK, et al. Male circumcision decreases high-risk human papillomavirus viral load in female partners: a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Int J Cancer 2013; 133:1247.

- Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; :CD003362.

- Auvert, B, Sobngwi-Tambekou, J, Puren, A, et al. Effect of male circumcision on human papilloma virus, neisseria gonorrhoeae and trichomonas vaginalis infections in men: results from a randomized controlled trial (abstract). Presented at the XVII international AIDS conference. August 2008, Mexico City.

available at www.aids2008.org/Pag/Abstracts.aspx?SID=288&AID=15881.

- Weiss HA, Thomas SL, Munabi SK, Hayes RJ. Male circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid, and genital herpes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82:101.

- Kaplan GW. Complications of circumcision. Urol Clin North Am 1983; 10:543.

If you’d like to find out more information or request an appointment with our private urologist in Berkshire or Windsor, please get in touch using our contact form available on the website or call 017 53 66 5415.